- Home

- Nairne Holtz

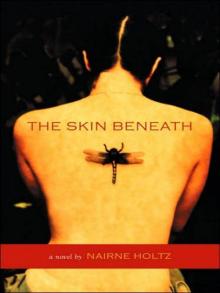

The Skin Beneath Page 7

The Skin Beneath Read online

Page 7

Sam smirks at him.

Omar frowns, and she realizes he hates being laughed at. He puts his elbows on the table and leans forward so he’s looking down at Sam. “You want the four-one-one on Chloe, this is it. We broke up. I bailed on her. I was cold. But I had to be. You see, the truth is—I wasn’t good enough for her.”

Sam almost laughs but stops herself; he’s one part charm, two parts threat. But his line? That’s a joke. She’s told girls, “I’m not good enough for you.” She said it regularly until a woman called her on it, told her, “You mean you can’t or don’t want to live up to my expectations.” The woman was right, which Sam demonstrated by never again speaking to her or feeding a woman that line. Now she repeats Omar’s words with a measure of incredulity. “You broke up with my sister because you didn’t think you were good enough for her?”

Omar continues to look intently at Sam. “When I was with Chloe, I didn’t think about anyone else. But we lived in different worlds. Sooner or later, she was going to get over her drama with her daddy, go back to school, and forget about me.”

“But she didn’t.” Sam sets her glass on the table, making a wet ring, lifts it, and makes another ring, overlapping the first one. What he is saying makes sense, but she doesn’t buy it. There is more here than his excuses. But how can she get him to tell her what he’s hiding?

Sam says, “Chloe never played by the rules. She might have gone into the escort business with you.”

Omar yells, “What? Chloe, a whore! That’s a nice way to talk.”

Sam concentrates on making another wet interlocking ring. She’s made him deviate from his script in which he intimidates her, then makes her feel sorry for him. When she speaks next, her tone is dry and mocking, a weapon from her father’s arsenal. “I was thinking more along the lines of running the business. She’d investigate niche marketing and order the fur suits while you handled security.”

Omar’s hands square into fists. “Go to hell.”

Sam shrugs. “If you won’t talk to me, I’ll talk to Romey.” She’s not afraid of him right now. It’s when he’s calm that he’s scary.

Omar doesn’t answer immediately. Instead, he shakes out his fists, as if he’s trying to toss away his anger. When he finally speaks, his voice is smooth and cold. “I’ll hurt anyone who gets Romey into trouble.”

Sam knows better than to ask her next question but can’t help herself. “You two are just friends?”

Now it’s Omar’s turn to look amused. “You need to check yourself. Romey’s not into guys.” The smugness leaves his eyes. “For real, Chloe would have dumped me if I hadn’t dumped her.”

Sam’s voice wobbles, “Who are you trying to convince?”

“This conversation is over.” Omar chucks a ten dollar bill on the table, grabs his cellphone, and fades out the door, not even bothering to talk to Joe.

Sam notices her fingers still stink of garlic. The lemons don’t mask the odour; they add to it. Omar is guilty. She just doesn’t know of what.

Even though Sam feels as if she’s coming down with the flu, she heads over to the anarchist bookstore. Before she sees Romey, Sam wants to find the conspiracy freak who was Chloe’s friend and talk to him. If anyone would know if her sister was investigating a political conspiracy, he would. Maybe the conspiracy freak even sent her the anonymous note. He’s black so maybe he’s a Tupac Shakur fan. Omar’s tattoo is probably just a coincidence.

Sam gets out of the metro station and trudges north on St. Laurent. She feels exhausted and is glad Librairie Alternative turns out to be close to the metro. There is no sign, only a sheet spray-painted with a black anarchy symbol, which hangs in a second-floor window. An industrial-looking glass door opens at street level onto a flight of stairs. At the top of the stairs is another door leading to the bookshop, which Sam enters. A square room lined with shelves holds a meagre selection of books. Sections are labelled “Feminism,” “First Nations,” and “Antiglobalization.” Most of the books are in English, but there are also materials in French and Spanish.

A woman sits behind a desk, reading a magazine. Beside her, an electric kettle begins to produce steam, which she either ignores or doesn’t notice. While the woman appears to be in her mid-twenties, she is wearing her dark blonde hair in slightly preposterous twin braids. Her pierced eyebrow only partly subverts her dairymaid look. Sam clears her throat to get the woman’s attention. She flips her magazine shut, and Sam sees she’s reading Bust, a feminist publication that is more trendy than political. In English, the woman asks Sam if she needs help.

“I’m looking for someone who works here or used to work here. All I know is he’s a conspiracy freak and he’s black.”

“You mean Francis? Yeah, he works here,” she replies. Her hand darts to her eyebrow piercing. The skin surrounding her eyebrow is puffy and pink like an insect bite.

She probably just got the piercing, Sam thinks. “Can you tell me what days he comes in?”

“We’re a volunteer collective, and we don’t give information out to people who haven’t been vetted. I mean, I have no idea who you are.” Her voice soars uncertainly at the end of her sentences, transforming them into questions, which Sam finds annoying.

Water from the kettle slops onto the woman’s desk, leading the Swiss Miss to at last unplug the cord and pour the boiling water into a nearby mug. She adds, “We have a bulletin board at the back where you could leave a message for him.”

Sam sighs. Who knows when this guy will read the message. And what should she say? “Do you have a pen and some paper?”

While the woman rummages through the desk drawers, the floor abruptly shifts beneath Sam’s feet. If she doesn’t sit down, she is going to pass out. She surveys the room for a chair but sees only the one behind the desk.

The woman places a pencil in front of Sam but no paper. “I’ll check the printer tray at the back.” She gets up.

Sam hauls herself onto a corner of the desk, taking care not to knock over the steaming cup of tea. She hunches forward, pressing her elbows into her thighs and the heels of her palms against her eyeballs. Vapour scented with cardamom whorls upwards from the tea, moistening Sam’s face and hands. The room and its contents flow away from her as she reels backwards. She feels as if she’s being pulled out of her body. She sees herself lying on an autopsy table, skin white, wrinkled, and powdery, as if it has been sprinkled with flour. Her hand is stained with ink: the officials are trying to identify her. Can’t they tell who she is from her tattoos? But the body on the table has no tattoos; Sam is wearing a different skin, an unmarked one. No, not exactly unmarked— she’s cut open in places. Blood and tissue trickle out of holes in her body. She tries to tell herself, it isn’t me. But the real her has escaped. Where has she gone?

“Are you okay?” The Swiss Miss is patting Sam’s shoulder.

“Would you like a cup of chai?”

Sam shakes her head. When the woman touched her, Sam’s fatigue and her dream, which felt more like a trance, disappeared like a palmed coin. Sam has the strange impression the woman made the hallucination happen, brewed it with her tea.

“I’ve got to talk to Francis. He was friends with my sister, who died. He may have information about her death,” Sam says. She wants to take charge of the situation, but instead she’s acting crazy and desperate.

The woman pins Sam’s face with cool, light-coloured eyes. Are they blue or grey?—they are no closer to one than the other. There is a skein of lines at the edges of her eyes suggesting the woman is older than she looks, is in her thirties.

The woman says, “What’s your name?”

It isn’t a question so much as an order. Her tone has lost all of its previous perkiness. The woman has shifted, traded one persona for another.

“Sam O’Connor.”

“I’m Amanda Tupper.” Her step, as she walks off, is light and on the balls of her feet like a ballet dancer. She returns with a piece of paper, which she gives to Sam, who writes

down her name and phone number. Amanda folds the paper into an origami crane, perches it on the desk. She says, “I’ll call Francis tonight.” After a pause, she adds, “You’re not from here, are you?”

“No,” Sam admits. She’s not going to tell the woman she’s from Toronto. From a few conversations at work, Sam has learned that trashing Canada’s largest city is a defensive sport with Montrealers.

Amanda sweeps her gaze over Sam. “Black clothing without artful rips. I’m guessing Toronto.”

Sam’s eyes drop to her black jeans and black Puma T-shirt and she immediately regrets doing so. Then she just doesn’t care; she wants to go home and sleep.

As Sam opens the door on her way out, Amanda calls, “If you want to talk, I’m here every week.” Then she picks up her magazine and pretends to read it. Sam wonders why this strange person would offer to see her again. People are friendlier in Montreal than in Toronto, but still. Sam’s boots slap down the stairs.

The next day, Sam calls in sick to work and sleeps until four o’clock in the afternoon. When she wakes up, she feels fine. Whatever strange bug she picked up is gone. There is a message on her voice mail: “The hawk is in flight. Tell the mice to take cover. I repeat, tell the mice to take cover. I can be reached at the following number…” The words are spoken by a man with an elegant baritone—a classical music radio announcer. Sam presses the number nine on her cordless phone to listen to the message again. What the hell does it mean? Who or what is the hawk? Who are the mice?

Sam dials the number left on the message. When a man answers, she informs him, without bothering to contain her annoyance, that he left a stupid message for her.

The man replies with a question. “Would it be safe for me to draw the conclusion that you are Sam O’Connor?”

He probably has call display. “It wouldn’t be dangerous. Who are you?”

The man clears his throat. “I’m Francis. I was a friend of your sister’s. I got a message you wanted to get in touch with me?“

Sam sighs. The conspiracy freak who works at Iibrairie Alternative. She guesses she owes Amanda a thank-you. “Yes, I’d like to talk to you about Chloe, preferably in person.”

“I can understand. You never know when the government’s listening in. The problem is I’m kind of occupied this week.”

“Are you busy right this second?”

Francis pauses and admits he is free. Although Francis agrees to see Sam, he doesn’t make it easy. He wants to meet her at a place called The Orange Julep, but he isn’t sure of the address. He says, “You can’t miss it. You’ll see it as soon as you get out of the metro.”

“I really don’t know Montreal very well,” Sam says.

Finally, reluctantly, he provides her with another address, which includes an apartment number, so she assumes it’s his home.

She grabs a map, runs out the door, and takes the metro to the northwest part of the city. When she gets out at a stop near the end of the orange line, she sees she’s next to a highway in one of those non-neighbourhoods that responded to urban sprawl by burping up car dealerships, fast-food chains, and big-box stores. As she walks along the highway, she is blitzed by the noise of wind and traffic. Commuters are heading home. The grey light of an overcast afternoon is slinking into darkness. Just before reaching an industrial sector, Sam turns right onto a tiny street. The address, written down on a piece of paper in her coat pocket, leads her to a cement high-rise, generica built by greedy developers in the 70s. She walks across the parking lot to the lobby, stopping just before the entrance at the sight of an old-timer sitting on a stool operating a ventriloquist’s dummy. The old guy is bald with fat orange sun freckles covering his head. He has a basset hound’s jowls, low-slung and wobbly, and he’s wearing a blue polyester suit that has been around since disco. Beside his white-shoed feet is a cardboard sign: “Presenting the Amazing Mister Horn and Jimmy.” The dummy is about three feet tall with red hair parted on one side and thick-lashed, brown glass eyes with thin, curved eyebrows. He is dressed in a plaid flannel shirt and tan trousers. In a strange way, the dummy reminds Sam of her father.

“Bon/our” the man calls to Sam.

“Hello,” Sam responds.

“Eh, you speak English. C’estpas grave. Jimmy and me, we’re English. Right, Jimmy?”

Sam watches the dummy’s head bob up and down. Then the dummy’s mouth flaps open, and, in a high, squeaky voice, he announces he’s hungry.

“A dummy eating food? Don’t be funny!” Mister Horn replies.

The dummy bangs its arm up and down. “I want my dinner. Give it to me. I do so eat!”

“You’re pulling my leg.” Mister Horn stretches his right foot.

The dummy slaps Mister Horn’s leg. “You liar! We went to McDonald’s on the weekend. liar, liar, pants on fire!”

Mister Horn stares up at Sam. “What do you say? You got some change for Jimmy and me to get a burger?”

Sam is unprepared for the sleight of hand changing a performance into a panhandling routine. When she reaches into her jeans pocket to get a coin, a rumpled five dollar bill falls from her pocket to the ground. She picks it up and hands it to the man. It is the most money she has ever given a panhandler.

She rushes into the lobby of the apartment building. When she gives beggars money, she can’t stand to look at them. She’s embarrassed but can’t tell if her embarrassment is for them or for her. Checking the piece of paper again, she punches the code of the apartment building into the intercom. An older woman answers. When Sam explains she’s meeting Francis, there is silence, then the buzzer goes off.

When she reaches his apartment on the fifth floor, the door is barely nudged open. Francis speaks to her through a thin strip. “Who is it?”

Sam grits her teeth. “Sam O’Connor. We spoke on the phone.”

Francis undoes a chain lock but doesn’t move the door open any further. He peers at her over the rim of his glasses.

“Can I please see some identification?”

Sam takes out her wallet and gives him her driver’s licence. She feels as if she’s crossing a border. Perhaps in his mind she is. At the same time, his behaviour seems affected.

Francis examines the licence for several minutes before giving it back to her. “I guess you must be who you say you are.” He speaks with reluctant generosity as if he is giving her the last piece of his favourite cake. In the background, Sam hears the older woman calling to him, asking him whom he’s talking to. Francis holds up a finger, then shuts the door in Sam’s face. A few minutes later, he joins her in the hall, having put on a coat and boots.

“This way.” He opens a nearby door for her with a flourish of his arm. Sam enters a stairwell, and they jog down several flights of whitewashed concrete stairs to reach the ground floor. He brushes past her, through a door that looks like a fire exit but doesn’t set off an alarm. Outside is a fenced-in area of grass where people are playing with their dogs. Francis strides by the grass and continues on away from the road, cutting through the backlanes. His legs are long so Sam has to run every few steps to keep up with him. When they get to the highway, they walk single file.

“What’s with the cloak and dagger?” Sam yells into the wind. “Why didn’t we go out the front door?”

Francis shivers, his torso twisting in a shimmy. “I never use the front door. I can’t bear the ventriloquist and his dummy.” His eyes flick skywards. “What, dear Lord, did I do to deserve them?”

Sam found them quaint yet understands his repulsion.

“Where are we going?”

“The Orange Julep for steamies.” Just ahead of them, an enormous orange fibreglass ball is perched on top of a hot dog stand. Sam and Francis make their way across an expansive parking lot to the ordering counter. Around them, people are sitting in their parked cars, and girls in stretch pants and roller skates whiz along the pavement carrying bags of food. When a man rolls down the window of his car, a skater girl hands him a hot dog and a cardboard ca

rton holding soft drink containers.

Even though the wind is raw and blustery, teenagers swarm the ordering counter. The air smells of potatoes and fried onions, and static-filled classic rock filters through poor-quality speakers. Francis orders the trademark orange drink and a hot dog from a teenager whose face is exploding with acne. Sam asks the kid for a large fries with mayonnaise. Out of a combination of new-found preference and a desire to seem native, she now orders her fries with mayonnaise. While she waits for their orders, Francis goes and sits down at a nearby picnic table. When the food arrives, Sam pays for it since he hasn’t given her any money.

Sam joins Francis. The wood of the picnic table soaks the back of her jeans, but she decides to just deal with it because he doesn’t seem to be the easygoing type. In his long parka, he won’t notice the dampness of their seats.

“This place is weird.” Sam says. “Don’t get me wrong— the food’s fine.” As if to prove it, she gobbles up a french fry.

Francis folds his arms together. “I love The Orange Julep. I know it’s kind of shoddy, but it was built in the Forties. Generations of teenagers have hung out here. We’re all addicted to a kind of post-war, Archie-comics nostalgia, I guess, because how can we be nostalgic about our own youth: the Vietnam War, the FLQ crisis, and Watergate?”

Although Sam has eaten in cafes that brand their mismatched dinnerware as ironic, and she remembers Chloe and James going to seedy taverns, in which he championed the working-class patrons, Francis’s take on eating at a cheap hot dog stand is unique. But he sounds reasonable. His voice is so dignified, so confident, so white. Meanwhile, Omar, who is Egyptian, talks like an urban African-American.

Sam studies Francis as he eats his hot dog in judicious bites, managing not to spill any chopped onions onto the table. From his reference points, she guesses he’s around forty. He’s average height and weight. With his wire-rimmed glasses and short, unfashionable afro, he isn’t a nerd so much as out of date. He is wearing plain black slacks, and Sam notices the corner of a pressed white handkerchief poking out of the right pocket of his grey button-down shirt. He does, however, have one strange feature, which Sam identifies only after several minutes—his earlobes are missing, and he appears to have been born that way.

The Skin Beneath

The Skin Beneath